The electrifying I cento passi (The hundred steps) tells the true story of Giuseppe "Peppino" Impastato, a Sicilian anti-mafia activist who was killed at the age of 30. Told with passion and clear-eyed convinction, it is an important and beautiful film - hopefully it can act as an antidote to the Hollywood portrayals of Italian criminal organizations which still recklessly glamorize it. As Gomorrah

The story begins when Peppino (Lorenzo Randazzo) is a young kid, beloved by his family and their friends. At a sunny lunch following a cousin's wedding, Peppino recites a poem, impressing the adults, and is then whisked around the courtyard by his favorite uncle (Pippo Montalbano). Young Peppino has only a vague sense that his family is involved in the mafia, though he's not sure what this means. One day, while he and his uncle are out, they hear a left-wing activist, Andrea Tidona (Stefano Venuti), publicly denouncing the mafia. Shortly thereafter, Peppino's uncle is murdered by - as Tidona explains - "those who want to take his place". Peppino, confused and deeply disturbed, is taken under Tidona's tutelage and begins his re-education.

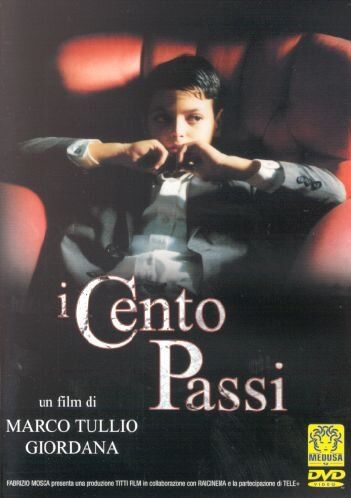

Brothers Giovanni (Paolo Briguglia) and Peppino (Luigi Lo Cascio) in the famous scene which gives the film its title.

The personal becomes political and back again.

We fast forward fifteen years, and Peppino (Luigi Lo Cascio) is now a young political activist in his small town's Communist Party branch. More and more, he sets his sights on the local mafia leaders, publishing manifestos and organizing demonstrations - even as the older Tidona warns him against stirring the hornet's nest (which Peppino ends up comically calling "Mafiopolis"). The film does a great job in capturing the perfect storm which propels Peppino into his now-legendary position as icon: youthful rebellion, especially against his father (a low-level mafia man), is fueled by 1960s leftist idealism (student protests everywhere!) and channelled into that most righteous of Sicilian political causes: anti-mafia work. Peppino is like any other angry young man, and it's the tragedy (or glory?) of his circumstances (as well as his wild courage) which lead him to eventual immortality. Using a local ham radio station, he gains notoriety and becomes a hero for the small town Sicilian fighting against the Goliath.

Meanwhile, he experiences various pressures - most notably from his father, Luigi (Luigi Maria Burruano), who becomes desperate, even violent, in his attempts to shut Peppino up. Once again, we have that feeling of seeing the personal through a prism of the political: Luigi is much like any other father who feels himself rebelled against, shut out and alienated by his son. His despair is so painful and so authentically private: no one, especially Peppino himself, can see quite how much his father suffers. There's a telling scene early in the film when Peppino is imprisoned with other demonstrators and is there heckled for being a wimpy "son of the mafia" - just in that moment, Luigi comes barrelling in with the policeman to get Peppino released. The son's humiliation before his peers, and his resentment towards his father (who was helping him!), is terribly palpable. This comes into play towards the end again when, following Luigi's death, Peppino is warned that the only thing keeping him from the mafia's hit list was his father. It's a universal tragedy - filial resentment and rebellion, parental sacrifice and self-pity - played out in the most volatile of settings.

Peppino at Radio Aut.

In town.

This schism between the older and younger generations, between the mafia and the anti-mafia, is interestingly textured with the visual of flying. Director Marco Tullio Giordana (who went on to make one of our favorite films, La meglio gioventù) peppers the film with symbols of flight: from the "national anthem of Mafiopolis" and Peppino's childhood favorite (Volaaaare, whoa whoa! Cantaaaaare, whoa oh oh oh!), to a number of scenes where characters look longingly at the nearby airport. Everyone, it seems, wants to escape things - poverty, Gaetano Badalamenti (Tony Sperandeo) and his goons, this "provincialism" (as one northern Italian hippie says) - but everyone is grounded, strangled even, by their circumstances.

Luigi Lo Cascio came crashing onto the Italian movie scene with this role, which he got straight out of Silvio d'Amico Accademia Nazionale d'Arte Drammatica and ended up winning the Donatello for. His wiry energy feels like a coiled spring - every so often, he explodes, and there are moments when you think of him as an otherworldly archetype for Angry Youth. Luigi Maria Burruano and Lucia Sardo are beautiful as Peppino's long-suffering parents - how they deal with the pressure is very different, and equally heart-breaking. Familiar faces - Stefano Venuti, Claudio Gioè, Ninni Bruschetta - were great to see, though their parts were relatively small, and Paolo Briguglia, as Peppino's younger brother, Giovanni, projected great sympathy.

It's interesting to compare this film, which is very serious and earnest, to anti-mafia films like the Neopolitan Mi Manda Picone, which makes its attack using satire and surrealism.

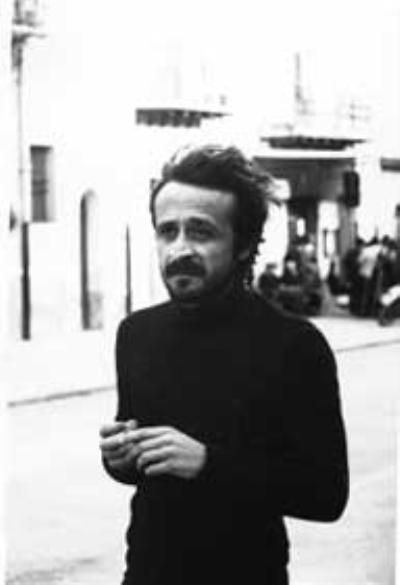

The real Peppino Impastato.

The real life ending: after 24 years, in 2002, the Italian government convincted Gaetano Badalamenti to life imprisonment for the murder of Peppino Impastato.

No comments:

Post a Comment