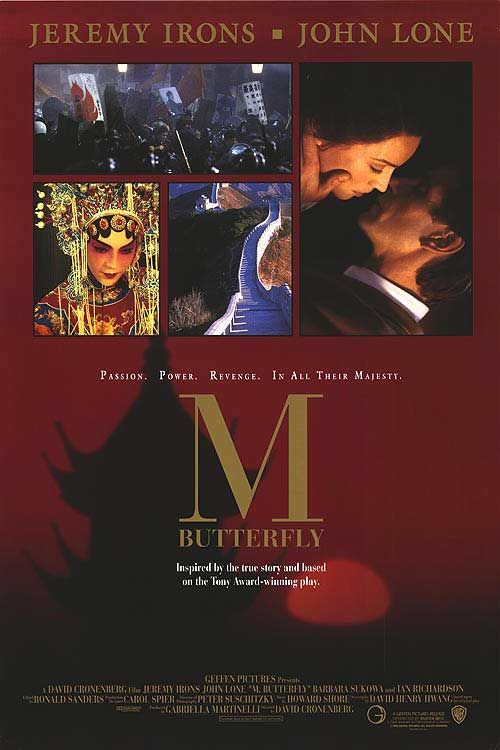

Madama Butterfly, that bothersomely melodic Orientalist opera by Giacomo Puccini, gets cleverly reinvented for a post-colonial world in David Cronenberg's 1993 M. Butterfly. A friend of ours misread the title as "Mr. Butterfly", and it's an apt slip, since M. Butterfly takes the original political and gender dynamic and upends it entirely. Just as we pitied the poor, stupid wretch that is Butterfly, suffering for a love that doesn't exist, so too do we pity French diplomat René Gallimard (Jeremy Irons) for getting well and properly played. Even if you could interpret his tremendous delusion and its terrible consequences as the just comeuppance of the White Man's Burden, there is no real pleasure in seeing Orientalism or male chauvinism get murdered quite so viciously - especially via one man as scapegoat. It's just sad.

Who is whose Butterfly, in the end?

Based on a strange, true story, M. Butterfly takes place in 1960s China, where the French embassy's accountant, René Gallimard, lives his life in a self-involved, self-perpetuated bubble of European expatriates. During one of the embassy's social nights, he sees a performance of selections from Madama Butterfly, as sung by a talented Chinese opera singer, Song Liling (John Lone). Song, presented as a woman, is clearly a man. And indeed, Chinese opera - much like English drama - was traditionally performed only by men. Gallimard, who will soon become the epitome of the ignorant Westerner, doesn't know this - nor does he understand the Orientalist implications of Madama Butterfly, and how they will play out in his deeply ingrained racial prejudices. While Song attempts to school Gallimard in these deficiencies, "her" demure elusiveness only incites his passions.

Soon enough they are having an affair, play-acting at the master/slave stereotypes of the "cruel white devil" and his "submissive Oriental woman". Tragically, Gallimard - seen as a spineless and lowly grub by his fellow white men - can use the Orientlist fantasy to become dominant and superior in the bedroom with Song. Tellingly, when Gallimard returns to Paris and falls into depression, claiming he was a "different man in China", his fellow Frenchman snorts into his wine and says, "Of course. You were white." Even more tellingly, Gallimard and Song's sexual relationship was so one-sided that Gallimard never thought to explore or pleasure Song's body - hence going for years (!) without realizing Song was a man. Although it is as clear as day that Song is a man, and that his very participation in this affair is done ironically - and, eventually, opportunistically (as Song begins to work as a spy for the Chinese government) - Gallimard is so self-deluded (or impassioned? or naive?) that he just never figures it all out. It is, probably, a testament to imperialism's deadly combination of arrogance and ignorance - you just don't realize how stupid you are.

Farewell, ancien régime.

But, just as Madama Butterfly's wretchedness is something to be pitied rather than reviled, so too does Gallimard end up a victim - a victim of the deception, as well as his own ignorance. We at the PPCC don't endorse Rudyard Kipling's Ballad of East and West (trumpeted by Gallimard's wife in an early scene), but neither can we watch an earnest, colorblind racist such as Gallimard be pilloried. He is not evil, he is just stupid. Indeed, while the film never pretends to sympathize with Gallimard's selfishness or his inability to see what's in front of him (both regarding Song as well as the brewing Cultural Revolution), it does acknowledge his tragedy. The finale, when Song's deception is made public during Gallimard's trial for treason, is devastating to watch.

There is one brief, touching moment when the love feels real. But still wretchedly sad.

There's an impulse from our warm and squishy side to seek out evidence that the love between Song and Gallimard is, somehow, somewhere, at least a little authentic. Unfortunately, in the passing, private expressions of Song during "her" moments with Gallimard, it is clear that Song feels only pangs of guilt - and, at best, a sort of baffled pity. In a reversal of roles, it is reminiscent of American sailor Pinkerton's private feelings for Butterfly. Similarly, Gallimard's love for Song is eviscerated and denuded (literally) as an expression of ingrained imperialism rather than anything more "pure".

The opera itself is used cleverly throughout the film - it is not over-relied upon, as we expected, but instead presents only touching counterpoints. For example, there is a scene when Gallimard, now living in wretched isolation as yet another anonymous white man in Paris, is shown listening obsessively to the opera. In particular, we are hearing the Humming Chorus - the same music which accompanies Butterfly's pathetically loyal, and ultimately futile, overnight wait for Pinkerton to return. While Song does magically appear at Gallimard's apartment during that scene, "she" brings with "her" an inevitable doom.

The film is built primarily on the strength of its script, which was based on a succesful play by David Henry Hwang. And it is dynamite! With far too many juicy dialogues about gender roles, sexual politics and post-colonialism to begin quoting them all here. The direction, by our odd favorite (why do we like Cronenberg so much? WHY?), was also at its smirking best - a notable smirk being for a scene where Gallimard's neglected, much-too-not-submissive wife begins to croon the Butterfly melodies, which cuts abruptly to a scene of Gallimard violently swatting a fly in his office. Heh.

If anything, this film shows that Gallimard's interpretation of Madama Butterfly as "sad, but beautiful" is just a symptom of his Orientalism. By turning everything around, the same story remains sad, yes, but in a very ugly way.

No comments:

Post a Comment