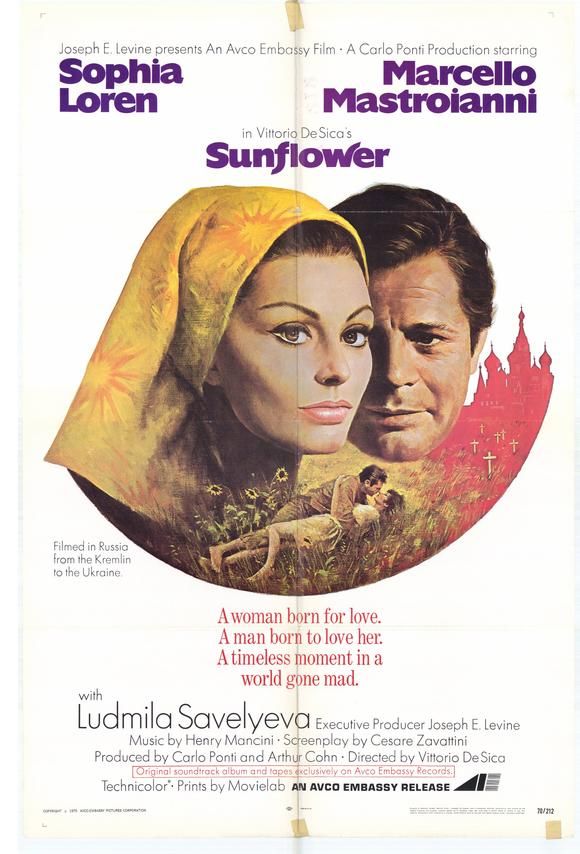

I girasoli (Sunflowers) is one of those epic WW2 love stories that spans decades and several countries. While hinting at stories like Doctor Zhivago, what with the sense of massive European history pulling and pushing lovers together and apart, it's not quite as good - but it is pretty decent. Its triple pedigree - De Sica, Mastroianni, Loren - makes sure that, while not great, it's good.

Early in the war, Neopolitan Giovanna (Sofia Loren) and not-Neopolitan Antonio (Marcello Mastroianni) are lovers on the beach. They decide to get married, since that'll give Antonio - who's convinced he'll soon be sent to the African front - twelve days of delay. "Who knows," Giovanna says brightly. "Maybe the war will be over by then!" Once the twelve days are up, however, the war is far from over (indeed, one of Giovanna and Antonio's honeymoon frolics is interrupted by a bridge-bombing on day 10) - and so they try to make Antonio seem insane. When that doesn't work, they resign themselves to the inevitable: Antonio is sent to the Russian front.

Years pass, the Italian soldiers return, but still no word from Antonio. Yet more years pass - Stalin dies (!), so it's 1953 (!), so (pencil scribbling) that makes it about ten years apart - and Antonio's mother gives him up for dead. But Giovanna, convinced he's still alive, decides to travel to Russia herself, armed only with her steely determination and an ancient wartime photograph of him. What she finds there (which you can probably Google, but we'll endeavor to be at least a little spoiler-free) is sad.

The film is soaked in shared history between Italy and Russia, and the rest of Europe, as both sides pick up the pieces after the war. De Sica emphasizes this common humanity and common heritage by using visual parallels repeatedly throughout the film: the train that Antonio leaves on, the train that brings news of the front, the train that backgrounds their post-war reunion. Antonio's limp, Giovanna's colleague's limp. The near frost-bitten Antonio collapsing in the Russian snow, becoming just one more fallen comrade as the army moves ahead. And, of course, the sunflowers of Russia ("Each sunflower represents someone who died here - an Italian soldier, a Russian soldier, a German soldier, civilians, men, women, children," a character helpfully explains) and the yellow mimosas of southern Italy. Or whatever those flowers are.

Anyway, the point is that this story is supposed to be a drop in a rainstorm: in Giovanna and Antonio's tender heartbreak, we're supposed to see all the thousands of other Giovannas and Antonios that were ripped apart by the war.

Generally, it works. Okay, yes, we cried. But it's not quite as magnificent as it aspires to be. The cinematography is glorious and large - many of the scenes are impressively enormous, capturing rolling fields, thousands of graves, the pristine blue sky. But we were also constantly distracted by De Sica's overenthusiastic use of the dolly. Had he just bought a new one or something? The jumpy zooming and ambitiously long takes (watch for one where a family moves all their furniture in a pick-up truck, and the camera manages to get all the way around the truck while, presumably, both truck and camera car are in motion). A story of this scale also warrants a richness of characterization which is lacking. While Sofia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni are everybody's favorites, and we certainly like them too, we felt that Giovanna and Antonio weren't clearly-enough defined, apart from their love story narrative. The mother-in-law was the barest sketch of a character.

So, all in all, a decently moving large-scale wartime story. Not mind-blowing, but not terrible. Kinda tearjerking. Like, tearnudging.

No comments:

Post a Comment