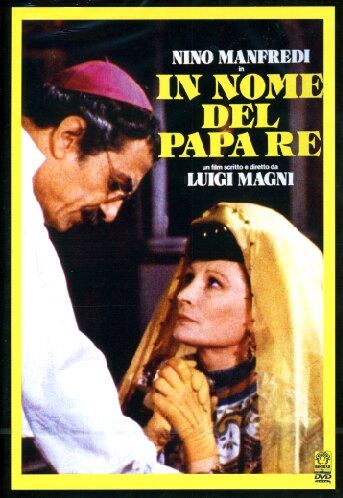

In nome del papa re (In the name of the Pope-king, though it could also be In the name of the father-king) is a fraught, strange, charming film. It's also a breath of fresh air in its portrayal of the clergy - long stereotyped as corrupt pedophiles or one-dimensional bigots. Quite the contrary, In nome del papa re's worn, frazzled anti-hero, Monsignor Colombo (a wonderful, as always, Nino Manfredi), seems more like an ancestor to the partisan-priests of WW2 neorealism than anything else. His tangled, unfortunate position - as reluctant collaborator to a reactionary Papacy, as reluctant father to an arrested revolutionary - is wonderfully charged, tragic and bizarre. His mannerisms also - cigar-chewing, Roman-slanging - recall the tinted glasses, smoldering cigarette and whiskey tumblers of the old SNL character, Father Guido Sarducci. In other words, the PPCC loves him and would totally go all Catholic for him. "What do you want from me?" Colombo demands, impatient. "A benediction? Want me to give you a benediction? You'll have to make it last!"

In the name of the Father (and father)...

...and son...

...and the Holy Spirit (of revolutionary Italia!).

But enough of priests, let's get to the plot. The year is 1867, and Rome is in full-on Risorgimento-style turmoil. (For those that don't know, Italy was created in 1861. The period of unification is called the Risorgimento, and featured a lot of bloody conquering of the various kingdoms and principalities - principal among them, of course, being the Papacy and its repressive reign over Rome.) Bombs are falling, Italian revolutionaries are hiding in the houses of the sympathetic bourgeois or getting their heads chopped off, and Monsignor Colombo (Nino Manfredi) is drafting his resignation letter as a Papal judge. "I just want to be a priest," he laments. "Which is hard enough, as it is." In other words, the good monsignor's lost faith in the Papacy's legitimacy as a secular authority. He's basically a closet Garibaldista, even though he won't admit it to himself. (Garibaldi being the general who led the armies which unified Italy.)

Meanwhile, across town, three revolutionary youths - among them the stormy, arrogant Cesarino (Danilo Mattei) - have learned that they're to be arrested and beheaded by the Papacy, following a terrorist bomb they (or someone) left under a barracks (killing dozens of Vatican soldiers). Cesarino's mother, the well-to-do gentlelady, the Countess Flaminia (Carmen Scarpitta), despairs - and flies immediately to Monsignor Colombo's house. And there she lays the bomb (no pun intended) of the Bestest Plot Device Ever on him: "Now you have two reasons to save him. One, because he's my son. And, two, because he's also yours."

Ah, yes. Yes, back in those heady, halcyon days of 1849, amid musket fire and the clash of armies, when the Vatican's foundations first shook under Garibaldi's assault, as she tended the wounded and he administered last rites to the dying, and they were so tired, and all they needed was a warm bed, and so on and so forth. Okay, we actually found that whole idea very romantic. But then, disrobing priests while battles rage around us in Garibaldi-era Rome - mm mmm!

One of the most badass scenes: the mother of one of the other condemned revolutionaries confronts Colombo. "You saved your son. You didn't save mine." When he tries to give her the Holy Communion, she leans back, "No. Not from you." BAM! Go, lady!

Anyway. Monsignor Colombo is clearly in a bind now, and the schmaltzy music which forever hounds his brooding bluntly announces the heartbreaking choices he must make. HEARTBREAKING, in case that's not clear. VIOLINS MUST BE PLAYED. How will he get Cesarino out of the clink? When guillotines fall with such ease, and "there are spies everywhere", and Cesarino announces that there are two things he hates in this world: "Absent fathers, and priests!" What's a guy to do?

The film is most effective when it's not REALLY ALL CAPS BLUNT - and certain schmaltzy moments could have been lessened if only the music track had been changed. But we can't complain. We even loved the soap opery final plot twist, if only because the lovely Nino Manfredi underscored everything so well with his restrained, effective performance. Manfredi's schtick - as he did so well in C'eravamo tanto amati - is the easy-going, sarcastic, vulnerable Roman with a heart o' gold. He lays that down as his main melody, and basically improvises around it - in this performance, peppering Said Roman with telling moments of weariness, worry and grief. Never is he explicit in these things, everything is turned into a joke. It's like his protective exoskeleton. And, of course, that makes it all the more touching. An example: one of the most poignant scenes is when his servant, a grizzled, Obelix-ish Serafino (Carlo Bagno), comes downstairs at dawn to find him sleeping, collar askew, at his desk. As Colombo grumbles himself awake, clearly exhausted, he laments the night before: freeing Cesarino, but not the other two revolutionaries, and thus doing a pretty half-assed good deed. As he hunkers down to eat his breakfast, he sees bite marks in it. "Did you eat this?" Serafino is aghast: "You think I'm giving you my leftovers? It must be the rats in the kitchen, they must have got to the pantry by now and given it a nibble." And Manfredi just looks at him, looks at the biscuit, eats, and then sighs, "They're God's creatures." Ha! Okay, maybe you had to be there.

Ah, 1860s Rome! Is that Trastevere that my eye detects?

Don't legitimize a false authority!

What's interesting about this film - a tame example of a 1970s Italian film, despite all the sexytimes on and off screen, with and without priests - is how, yet again, political engagement is portrayed as complicated, messy and doomed. We saw this in Lina Wertmuller's incredible Love and Anarchy, a film which explored a would-be assassin of Mussolini in the days before the deed. Both films, which follow the "good" guys (pro-Unification priests, anti-Fascist anarchists), essentially end badly. It's very sad. And both films offer an apologetic coda, promising the good things that actually did occur to those movements post-movie timeline: i.e. the eventual unification of Italy and demise of Papal power; the eventual liberation of Italy by the Americans in 1945, and the death of Fascism. Which makes us wonder. Why are these films, both about real periods and real movements that "won", so pessimistic? Is it just commentary on extreme political activism per se? The inevitable fall of the zealous anarchist/partisan/Garibaldista? Hm.

No comments:

Post a Comment