Disney movies, and Disneyism in general, share a couple defining traits:

- First, orphandom and the destruction of the parent/protector. Most Disney hero/heroines we can think of have been parentless or violently orphaned (Mowgli, Dumbo, Bambi, Simba, Aladdin, Nemo), and this is usually a big part of the plot (and legend-ness of these characters - e.g. the death of Bambi's mother, or Simba's father, are epically remembered childhood proxy-traumas - seriously, we at the PPCC can't watch this scene without choking up).

- Second, manipulation. Oh my Looord, manipulation.

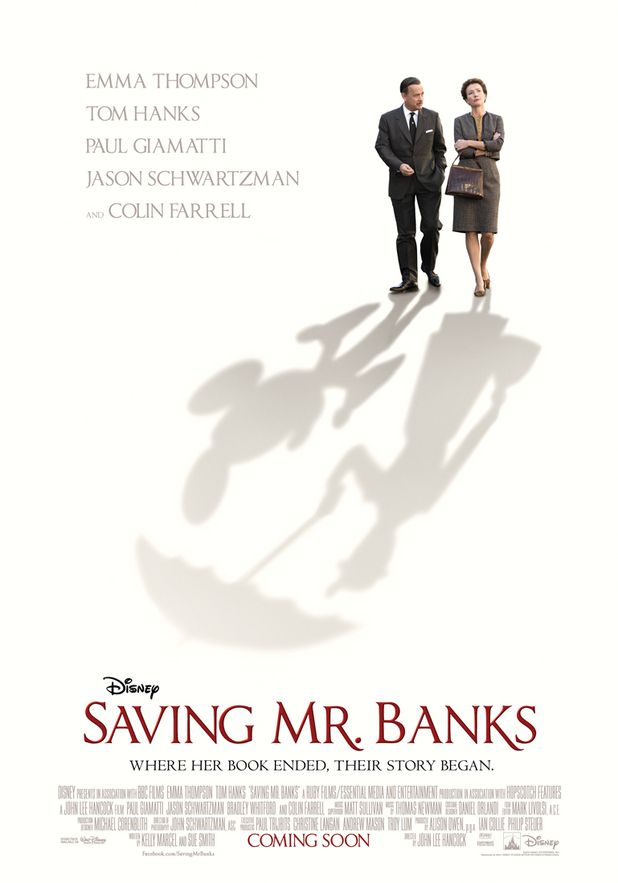

So it shouldn't come as a surprise that Saving Mr. Banks, a Disney film about Disney films, should feature - at its core - parental detsruction and consequent trauma. It follows a prim pedant named P.L. Travers (Emma Thompson), author of the Mary Poppins books, as she battles over creative control - and life philosophies - with the sunny, Zen Fascist-ish forced optimism of the Disney Empire. SMILE, DAMN YOU, SMILE. Or, as the Dead Kennedys put it, ALWAYS WEAR THE HAPPY FACE. MELLOW OUT OR YOU WILL PAY.

It's a tolerable film, though not nearly as self-aware and glorious as the other Disney-on-Disney film, Enchanted. Where Enchanted snarkily lampooned common Disney tropes - most centrally, the Relentless Optimism stuff - Saving Mr. Banks, instead, is fully (blindly?) behind them. As a result, it feels a little lifeless - even a little dishonest. We're meant to believe that the power of Disney - the plush toys, the California sun, the well-manicured everything - will eventually break into and heal even wintry P.L. Travers's heart. A heart, mind you, that was broken long ago by a charismatic, boozey dreamer of a dad, played (ineffectually) by Colin Farrell.

It's also partly a UK-versus-US thing, with each side (Travers and Walt himself (played distractingly by Tom Hanks as Tom Hanks)) being an embodiement of the national caricature: "terminally enthusiastic American"-ness (as the PPCC was once called!) versus drab, rainy, pessimistic Britishness. It's the triumph of southern California optimism therapy (redemption! forgiveness! pat endings!).

What's annoying is that the manipulation does work. We at the PPCC ugly-cried at this, sobbing as Emma Thompson sobbed, choking up as Paul Giamatti (!) the Soulful Driver choked up. Damn you, Disney! But this saccharine emotionalism leaves a bad taste as well, and it can't hide some of the film's flaws. Many characters are only rough, one-note sketches. Both Hanks and Thompson - both very loved by the PPCC - are unable to muffle their starshine: they seem like themselves, not like Disney and Travers. The childhood flashbacks are needlessly protracted: we know that "Mr. Banks" - Travers' father - is meant to, somehow, need saving. Watching his slow decline is (1) very slow indeed, and (2) a little difficult to sympathize with.

One interesting point was the link back to Travers's father's Irishness, and his adherence to a mystical, dreamy philosophy. Oh, Ireland. Oh, Erin.

This world is just an illusion, Ginty, ol' girl. As long as we hold that thought dear they can't break us, they can't make us endure their reality, bleak and bloody as it is. Money, money, money, don't you buy into, Ginty. It'll bite you on the bottom.It's ironic - tragic even - then that this story is essentially about that daughter giving into that corporate, "money, money, money" spiral. Or maybe the film is a marriage between money and embracing (even manipulating) the illusion? That'd certainly be Disney in a nutshell.

No comments:

Post a Comment