Allonsanfàn is a wry, strange look at the absurd tragedy of radical Italians. It technically takes place in the early 19th century, but it could be just as home in the 1860s, 1920s or 1970s. In fact, especially the 1970s - a decade in which domestic terrorism killed Aldo Moro and laid bombs in Bologna's train station. A decade where the idealism of 1968 had ripened into a hyper-violent, extreme nihilism (both on the Left and the Right), where killing became a currency of discourse. (Thanks, Paul Ginsborg, by the way, for teaching the PPCC about modern Italian history! Seriously, readership, A History of Contemporary Italy is wonderful.)

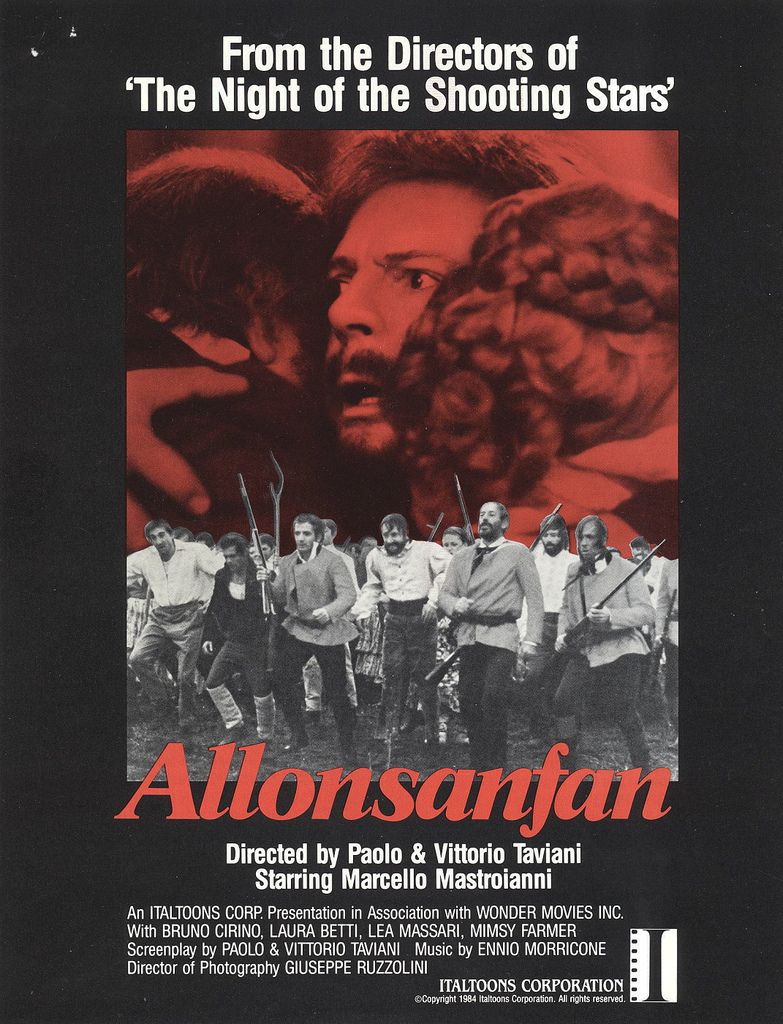

Anyway, in Allonsanfàn, we follow a disillusioned, weary and aging radical, Fulvio Imbrani (Marcello Mastroianni), as he repeatedly tries (and fails) to extricate himself form his former revolutionary life. This is often to grotesque or comedic results (such as when he makes a suicide pact with one fellow comrade, only to let the other guy go first), though - as is the usual style of 1970s commedie all'italiana - it's also very sad, beneath everything. The aristocratic Fulvio stumbles out of prison one day, feverish and exhausted, narrowly avoiding a grim fate at the hands of the state. His revolutionary comrades likewise almost behead him, thinking he had spilled all their secrets. When this is proved false, he is left to mend in the comfort of his big fancy bed in his big fancy mansion. And big fancy mansions - they are hard to say no to.

Indeed, Fulvio's ideals - which were already a little brittle - now crumble under the weight of this material comfort. Of course, this gnaws at him - aren't those big fancy chandeliers just symbols of oppression? And his poor nanny, still making his bed and doing back-breaking agricultural labor outside? Fulvio's strength of opinion, though, has been broken out of him. Or maybe he's just tired of being indignant and sure of everything, because he proceeds to embark in a misguided, frequently half-assed adventure to cut his old ties. We found ourselves snickering, sometimes with disgust, sometimes with glee, at Fulvio's silliness, selfishness and pitiable state - and we found ourselves constantly grafting this story onto the wider meaning of 1970s Italian politics, messy and unfortunate as they were. "How can we live in this world?" one earnest revolutionary laments. "When everyone seems asleep, and we're the only ones who seem to have woken up?" It's a sad, slightly delusional statement, and Fulvio's in the unfortunate position of recognizing the idealists' misguided attempts to (for example) free the Southern peasants, while not having the courage or ability (or good luck!) to get free of their grasp. He's made his bed, and now he's going to LIE IN IT, FOR THE LOVE OF GOD.

Allonsanfàn himself turns out to be a character, a young revolutionary (Stanko Molnar), who is the most dedicated, the grimmest, and, ultimately, the most delusional. A stand-in for the young, violent Red Brigades? Allonsanfàn is also, oddly, named after the first two words of La Marseillaise ("Wake up, children!") - indeed, the strains of revolutionary France are an important reference for the revolutionaries of this film. (In the way that the Paris Commune inspired the 1968 Italian idealists?)

Marcello Mastroianni is, as usual, wonderful in this, aging charmer that he is. Indeed, he channels that same world-weariness that we saw in Una giornata particolare, as well as the sense of a man trapped in an almost Kafka-esque surrealist nightmare, much like his role as the doomed bricklayer from Dramma della gelosia. The music by Ennio Morricone, particularly the theme of the revolution, was also incredibly catchy and wonderful: this scene, where an embittered Fulvio meditates on his former comrades, was just wonderful. "I've healed. I've changed." Brrr, lovely!

No comments:

Post a Comment