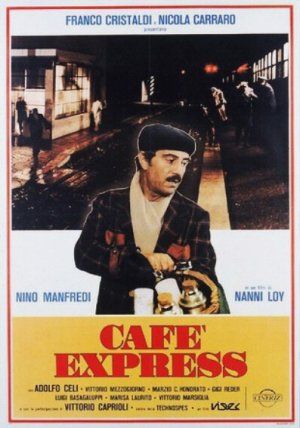

Like a number of commedie all'italiana, Café Express is a tragedy dressed up as a comedy. Also, like other picaresque Neopolitan Odysseys (e.g. Mi manda Picone), dissembling, poverty and surreality factor heavily.

Michele Abagnano (Nino Manfredi) is an illegal coffee vendor riding the night train between Naples and Rome. With his broken shoe and wooden arm, he cuts a sorry figure. Though, since he's played by the charming Manfredi, he's also wonderfully lovable, always ready with a joke and sympathetic ear. The film ambles along, dropping in with Michele as he visits the various characters in the various cars. In this way, and the fact that it takes place overnight, the film resembles an episodic, nocturnal, ensemble piece like Jagte Raho or After Hours: that is, it mixes the strange with the immoral with the funny, all steamed up with some schmaltzy philosophizing on the nature of man.

With each car, Michele's story changes: in one, his wooden arm is a war wound, in another, an injury received as he saved children from a burning home. Even if he's a warm and gregarious presence, he's also evasive and, thus, mysterious. The only thing we know for sure is that he has a 14-year-old son, Cazzillo (a very cute Giovanni Piscopo), with a congenital heart defect - we know this for sure because we actually meet Cazzillo, as rascally as his father, when Michele finds him shaving in the train's bathroom. (Okay, that whole scene was adorable.)

Things take a very sour turn after Michele pisses off a small gang of thieves, and the film swings from a sentimental Italianate tragicomedy to an enraged screed against an unjust society. As well as a plea for magic(al) realism as a weapon against (Anglo-Saxon? oligarchic?) hegemonic notions of "reality"? Maybe. As Obi-Wan Kenobi would say, "So what I said was true. From a certain point of view." Similarly, Michele - and, to his horror, his son, Cazzillo - live by this creed of a malleable reality. It certainly feeds the stereotype of Neopolitans as knavish story-spinners, and it certainly makes for great surrealist cinema. What is the truth? We'll never know for sure. And, even if we did, would it change the tragedy (or funniness) of the situation?

Props to the final shot, with the self-posessed, urchiny Cazzillo making his way through a 1970s Rome, a little hawk in search of prey. That was fabulous. And props, as always, to lovely Nino Manfredi, our favorite interpreter of Romanness (even though, in this film, he's Neopolitan - and whoa! that accent!).

(Though Italian speakers can watch the movie here.)

1 comment:

Sounds like an interesting movie. Must get it.

Post a Comment