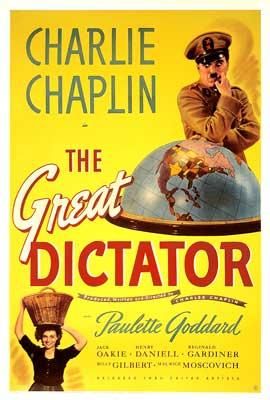

Strange, surreal and impassioned, Charlie Chaplin's The Great Dictator is part satire, part slapstick, part indignant humanitarian rage. It's still an edgy film seventy years on, because it's always rare to see a gutsy director take a direct jab at current events. Hitler invaded Poland in 1939. A year later, The Great Dictator came out. And no one in this film had any idea how the war would turn out (!).

With the fictional "Tomania" and "Bacteria" standing in for Germany and Italy, respectively, The Great Dictator follows the dual lives of Tomania's maniacal dictator, Adenoid Hynkel (Charlie Chaplin), and a Jewish barber (Charlie Chaplin, again) living in a Tomanian (or should we say Tomaniac?) ghetto. Beginning in World War I, the unnamed barber - a bumbling klutz of a soldier - manages to save a Tomanian pilot, Schultz (Reginald Gardiner). After some clowning around and a plane crash, the barber suffers memory loss and spends most of the interwar period in a hospital. When he returns, he finds his neighborhood radically different: it's now a violent, volatile ghetto where stormtroopers regularly harass shopowners and families, threatening them with concentration camps.

Man at war. Sort of.

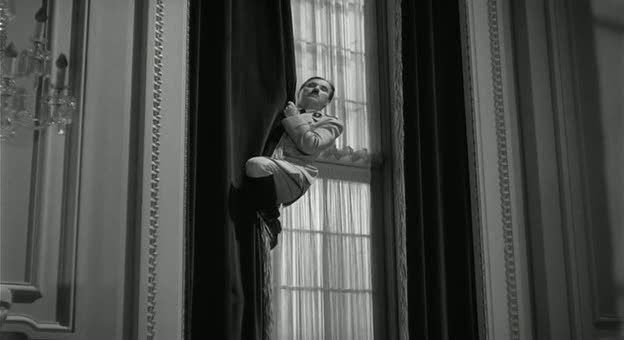

Hitler, er, Hynkel, in a private moment.

While the barber's story is at best tragicomic, and follows a genuine narrative arc full of suspense and suffering, Hynkel's story is just a blow-by-blow mockery of Hitler's Greatest Hits. There's his infamous speeches to the screaming hordes, which Chaplin performs in full-on pidgin German ("Der bratwurst und der saurkraut!" Hynkel screams). There's his meeting with "Benzino Napaloni" (Jack Oakie), and the (very funny) ego war between them ("Der cheesy ravioli!" Hynkel seethes). And there's a bizarre, ridiculous sequence in which a daydreaming Hynkel dances daintily with an inflatable globe.

We were about to comment on the oddly smoking chemistry between Chaplin and Goddard, and how oddly sexy Chaplin was as the barber, but then we read about Chaplin's ladykilling on Wikipedia, so... um, I guess we're not the only ones who were a bit charmed.

All of the Hynkel scenes are genuinely funny; they are bizarre, eviscerating, silly and smart, such as when Hynkel's propaganda man, "Garbage" (er, Goebbels), instructs Hynkel in the psychological warfare they intend to wreak on Napoloni to ensure the latter's feelings of inferiority. Napoloni's easy evasion of their tactics, such as putting him in a low-seated chair ("They've-a put me in-a the toddler chair!" Napoloni mutters), is whimsical and fun.

Some great moments between Hynkel and Napaloni. That cheesy ravioli!

A rare funny moment from the Jewish barber plotline; Mr. Jeackel (Maurice Moscovitch) was absolutely lovely, and him climbing into the crowded trunk was the best!

All of the barber scenes, on the other hand, cut too close to be funny. In a post-Holocaust world, it's hard to keep your hackles down when the barber is beaten up for refusing to paint "JEW" on his windows. Chaplin goes for some jokes here, mostly of the slapstick kind (the barber being a very close relative of the disaster-prone Tramp), but the real-life references are too somber. Chaplin is aware of this too, and indeed the barber's story is allowed to be frightening and sad at times, such as when the barber and his crush, the feisty laundry girl Hannah (Paulette Goddard), have their first date interrupted by a declaration of Kristallnacht. Watching their falling expressions while the terrified crowds flee into their homes, effectively emptying the street behind them, is truly horrible.

Some less funny scenes. The Jewish barber is captured and sent to a concentration camp (!).

Things become progressively more somber...

The film is more message than joke, and so it ends with the barber - and his (in)famous sermon to the masses in the name of peace and love. Some critics, such as Ebert, say this ruins the film - basically turning it into a mouthpiece for Chaplin's personal political beliefs. (Other people, like zany Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, note the interesting parallels between Hynkel and the barber in how they sway the masses.) Our take was much more meek, partly because we were feeling a little emotionally bruised by the end of this film, and earnest pleas for justice and humanity were a welcome respite from all the preceding fictional and non-fictional insanity.

1 comment:

Yaay some Chaplin love, I really didn't mind the speech at the end, it was impassioned and atleast got his view out. This was kinda similar to Raj Kapoor's earnest speech at the end of Jagte Raho, ohh gawsh bringing up references to my gargantuan Chaplin-Kapoor essay! But i like this film a lot better than the rest of Chaplin's talkies!

Post a Comment